Recently, a wave of viral TikTok videos is pulling back the curtain on the luxury fashion industry, claiming that about 80% of all branded goods – from Gucci to Lululemon – are made in China. One video, posted by the account @senbags2, quickly racked up over 10 million views before being taken down on not long after. But that didn’t stop the video from being duplicated and shared across multiple platforms.

But how accurate is that claim? Chinese manufacturers, once silent partners in the production of high-end goods, are now openly advertising their role in crafting products for Western luxury brands. These videos showcase factories producing items that closely resemble luxury goods, offering them directly to consumers at a fraction of the retail price. This trend is challenging the traditional narrative of luxury branding and pricing.

The Viral Trend

On platforms like TikTok, Chinese factories are sharing behind-the-scenes footage of skilled workers stitching handbags, finishing shoes, and assembling garments that they claim are made for top-tier European houses. Some even name-drop brands like Hermès and Birkenstock, suggesting that their direct-to-consumer (DTC) offerings are made with the same materials, machines, and labour—just without the brand name. And the prices are only a fraction of what you’d pay in the market.

While many of these products are legally unbranded or design-adjacent, the marketing plays off the idea that you’re buying “the same thing” without paying for the label. While the knockoff bag you’re ordering could be great quality, it definitely won’t be an Hermès.

What ‘Made in Italy’ and ‘Made in France’ Really Mean

Labels like “Made in Italy” or “Made in France” evoke visions of artisanal workshops and centuries-old craftsmanship. In reality, the bar for these labels is often more technical than romantic. EU regulations allow a product to carry a “Made in” label if its final substantial transformation happens in that country—even if materials, labour, and earlier production stages were outsourced to places like China, Turkey, or Vietnam.

That means a luxury handbag could be constructed with Chinese leather, stitched in Tunisia, and assembled in Italy—then sold as a 100% Italian-made piece. Some brands leverage this loophole to protect margins while maintaining the illusion of European exclusivity.

Some luxury brands have quietly turned to an interesting workaround: bringing in skilled labour from China (mostly from Wenzhou) to work in Italian factories. These Chinese workers are often employed in small workshops on the outskirts of cities like Prato and Florence. The result? A product that technically qualifies for the “Made in Italy” tag—because it was assembled there—even if much of the labour force, materials, and methods mirror those found in Chinese factories. It’s a legal loophole that allows brands to retain the allure of European craftsmanship while tapping into a globalised, cost-effective workforce.

The Power of the Logo—and the Market It Commands

While Chinese factories may offer high-quality dupes, there’s one thing they can’t legally replicate: the logo. And in the world of luxury, the logo isn’t just decoration—it’s a form of currency.

Take the Hermès Birkin bag. It’s not merely made in France; it’s part of a globally recognised value system. A Birkin isn’t just a handbag—it’s an asset, a status symbol, and for some, a better investment than stocks. One study showed:

- S&P 500: ~8% annual return

- Gold: ~5%

- Birkin bags: ~14%

Unlike most luxury goods that depreciate, the Birkin has managed to become a wearable hedge fund.

Each Birkin is handmade by a single artisan, taking around 48 hours of meticulous craftsmanship. But before they even touch a Birkin, artisans train for up to five years. And even if you’ve got cash in hand, you can’t just walk into an Hermès store and buy one. Because you don’t choose Hermès—Hermès chooses you.

To get a Birkin, you need to play the long game: spend thousands on scarves, shoes, and belts. Build a relationship. Show loyalty. Then maybe, just maybe, they’ll offer you one. It’s exclusivity disguised as a shopping challenge, and it works. This is the psychology of scarcity—and no one does it better than Hermès.

And let’s not forget, Birkins are more than arm candy. They’re diplomatic tools, tokens of power, and occasionally, the quiet part of corruption (remember the 1MDB corruption case involving Rosmah Mansor’s 272 Birkin bags?). From political favours to hush-hush deals, they’ve been handed over not just for birthdays, but for silence. Try doing that with a replica.

This is the power of the brand: perception, prestige, and social cachet all wrapped in one. Without it, it’s just a bag.

Luxury Prices for Made in China

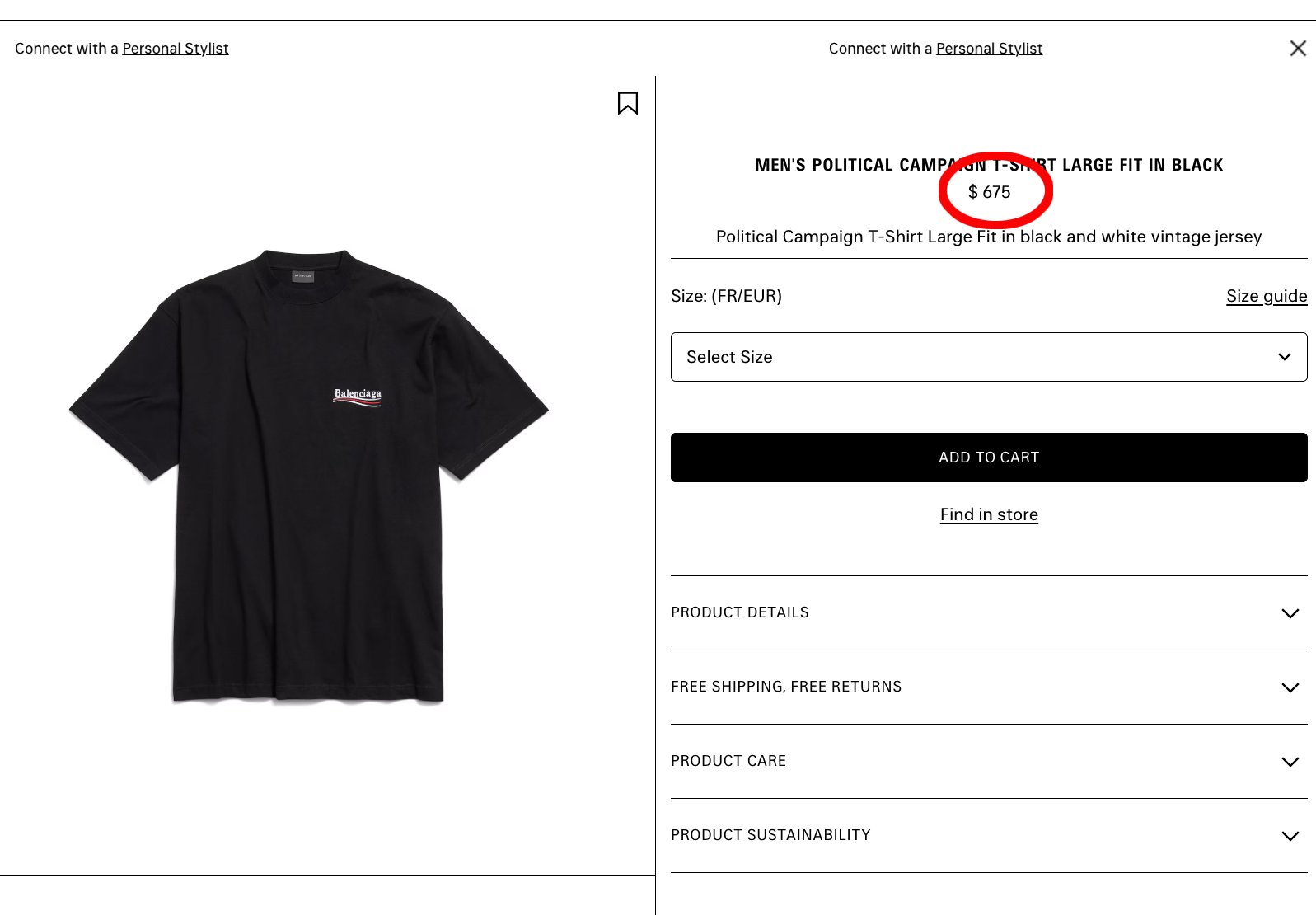

Luxury brands are under increasing pressure in 2025—from both ends of the market. On one side, economic uncertainty and shifting consumer values mean younger, savvier shoppers are questioning why a cotton T-shirt should cost $700, especially when the same factories in China or Vietnam are producing similar quality at a fraction of the price.

Investigations have revealed significant markups; for instance, a Dior tote bag priced at $2,780 was reportedly assembled for just $57. Such disparities have led consumers to question the fairness and transparency of luxury pricing.

On the other side, social media has democratised transparency, with viral videos pulling back the curtain on where and how luxury goods are really made. Add to that the rise of direct-from-factory sales and “dupes” proudly flaunted on TikTok, and the mystique of exclusivity is starting to wear thin. In an age where authenticity and ethics can matter more than logos alone, luxury brands are being pushed to justify not just their prices, but their entire business model.

Moreover, some luxury brands have outsourced entire product lines to countries outside the EU. Balenciaga’s popular Triple S sneakers, for example, were initially manufactured in Italy but later production was moved to China in 2018. Despite the change in manufacturing location, the sneakers maintained their $850 price tag. Balenciaga justified the move by stating that Chinese factories have the expertise to produce a lighter shoe, but the decision sparked debates about quality and value among consumers.

Luxury Brands Under Pressure

Now, in the first quarter of 2025, the luxury industry is facing a significant slowdown that has hit even top brands hard, as price increases have reached a ceiling, negatively affecting demand from aspirational luxury consumers.

LVMH reported a 3% decline in first-quarter sales in 2025, with its share price falling over 38% in the past year, as the luxury boom begins to cool. Hermès, however, saw a modest 2% rise in share value, overtaking LVMH to become France’s most valuable company. Prada, Kering (owner of Gucci), and others are now grappling with how to maintain brand mystique in an increasingly transparent world.

The Future of Luxury

As Chinese manufacturers step into the spotlight and younger consumers demand more transparency and value, luxury brands are being forced to reckon with their “dirty little secret”: that the price tag is more about perception than product.

Whether this will lead to a redefinition of luxury or simply a more fragmented market remains to be seen. But one thing’s clear—when the factories go viral, the logo alone may no longer be enough.