Did you know that the original version of Monopoly was invented not by The Parker Brothers, but by Elizabeth Magie? In 1904, Magie patented a game called The Landlord’s Game, which aimed to educate players about the dangers of monopolies and wealth inequality. Unlike the cutthroat capitalist version we know today, The Landlord’s Game had two sets of rules—one that encouraged the now-familiar monopolistic competition and another that promoted wealth-sharing and cooperation.

It wasn’t until the 1930s, when Charles Darrow modified the game—essentially using only the monopolistic rule—and sold it to Parker Brothers, that Monopoly became the iconic real-estate game we play today.

The inspiration for the game

Elizabeth Magie – or “Lizzie” Magie – created and patented The Landlord’s Game in 1904 as a response to her deep concern about the growing economic inequality in America and the rise of monopolistic practices. Inspired by the ideas of economist Henry George, who advocated for a single tax on land to combat wealth concentration, Magie wanted to design a game that would both entertain and educate people about the dangers of unchecked capitalism. She believed that a board game could serve as a powerful tool to illustrate how monopolies could trap individuals and stifle opportunity.

Magie spent years developing The Landlord’s Game, which was a critique of the capitalist system and a call for social reform. The game featured a square board with properties to buy and develop, and has two sets of rules: monopolist and anti-monopolist. In both versions, the objective was to accumulate money, but in the anti-monopolist version, players worked together, while in the monopolist version, the goal was to bankrupt opponents by controlling key properties.

Magie’s game included several phrases that reflected her belief in economic justice and the critique of monopolies, like:

• “The Landlord is a Parasite” highlighted Magie’s critique of those who accumulate wealth through landownership without contributing to productive labour.

• “Rent is the price of the privilege of occupying the earth” which is the theory that land value should be taxed for the common good.

• “Labour upon Mother Earth Produces Wages” encapsulated the idea that land and natural resources should be the common heritage of all people, and that wealth should be distributed more equitably.

Players had to agree on which set of rules (Monopolist or Anti-Monopolist) they would follow before starting the game. This was an essential decision, as the two rule sets created very different gameplay experiences.

If players chose the non-monopolist rules in The Landlord’s Game, the focus shifted from competition to cooperation. Rather than aiming to bankrupt opponents, players worked together to maintain a fair economy. Rent paid on properties was shared among all players, and wealth was distributed more equally. Players built communal improvements, helping everyone succeed while preventing any one player from gaining a monopoly. This version reflected Magie’s vision of promoting shared prosperity and social equity over individual accumulation.

Why “Landlord’s Game” didn’t take off

Magie’s version of The Landlord’s Game was not commercially successful due to several factors. It had limited marketing and distribution, as Magie self-published the game and circulated it mostly among niche groups interested in Henry George’s economic theories.

The complexity of the game, with its dual-rule system, made it difficult for casual players to grasp. Additionally, its educational focus on critiquing monopolies and wealth inequality may not have appealed to those seeking simple entertainment.

Magie also lacked the business expertise to scale the game commercially, and the themes of social reform were ahead of their time, failing to resonate with a broader audience. As a result, the game remained a niche product until the 1930s when Charles Darrow came across it through a friend who had played it in a social circle in Atlantic City.

Enter “Monopoly”

Inspired by the game, Darrow saw its potential for commercial success but believed it needed some modifications to appeal to a wider audience. He simplified the rules, focusing entirely on the competitive, wealth-building aspect and eliminating the cooperative version of the game. He did so without Magie’s knowledge or involvement. Darrow also renamed the game Monopoly, changed the properties to reflect real locations in Atlantic City, and streamlined the mechanics to make it more accessible and fast-paced.

After making these changes, Darrow pitched Monopoly to Parker Brothers, who initially rejected it. Parker Brothers had a solid reputation for producing a variety of games, including popular board games such as Clue (released in 1949) and Risk (released in 1957), which became major hits later on.

Undeterred, Darrow self-published the game, and it quickly gained popularity. Seeing its success, Parker Brothers reconsidered and eventually bought the rights to Monopoly in 1935 for US$1,000. Darrow also earned royalties, which allowed him to continue benefiting from the game’s success.

Magie, who had patented The Landlord’s Game in 1904, was unaware of Darrow’s version until after Monopoly became commercially successful. She later tried to assert her ownership of the game’s concept, but by then, Monopoly had already been acquired by Parker Brothers and became a massive success. Despite this, Magie’s contribution to the creation of the game was largely unrecognised at the time, and she received very little compensation for her work.

Playing other versions of “The Landlord’s Game”

While we’ll never get to see or play Magie’s original game, there are several board games that, like The Landlord’s Game, explore themes of wealth distribution, economic inequality, and alternative economic systems, some of which emphasise cooperation over competition or offer a critique of capitalism.

Monopoly: The Socialism Edition (2017): Ironically, this variation of Monopoly is closer to Magie’s original game. Instead of players trying to monopolise properties, players collect resources to help fund societal services, which reflect the values of socialism, focusing on public welfare.

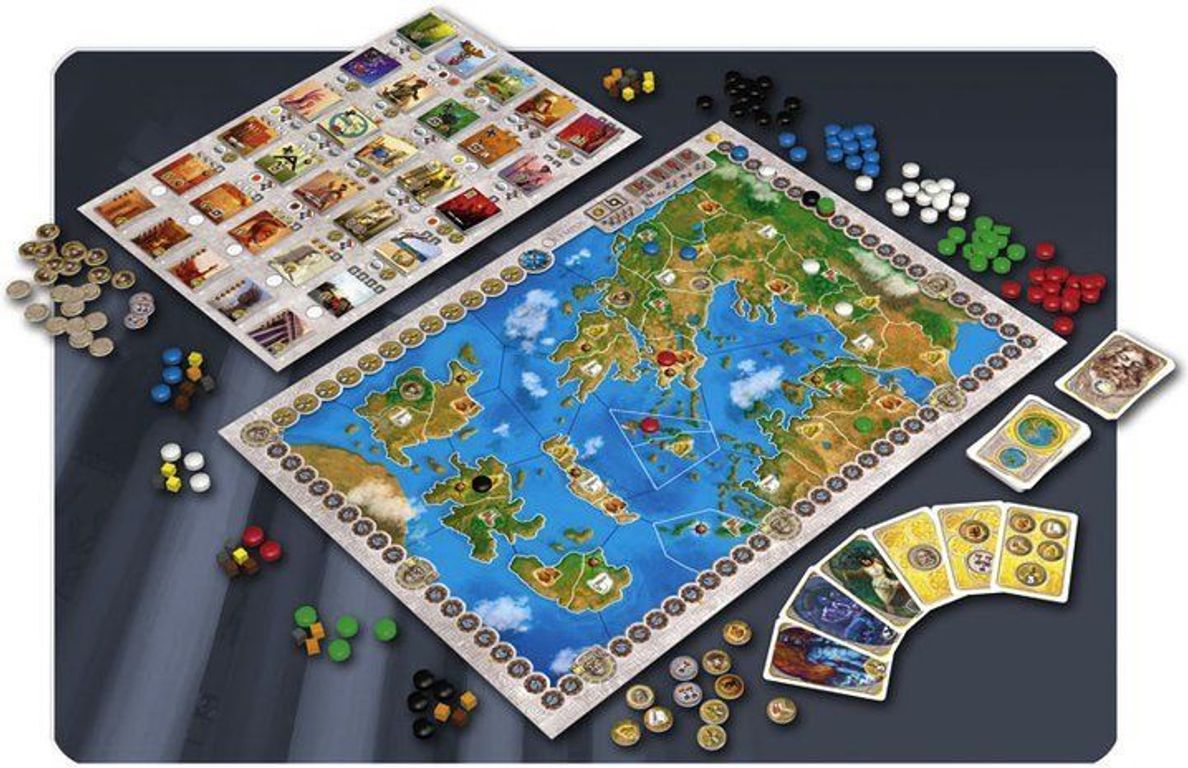

Oikoumene (2015): Simulates the rise and fall of civilisations through economic and political strategies. Players must balance between building a civilisation and maintaining ecological and social stability.

Power Grid (2004): This game focuses on building energy networks, where players compete to supply energy to cities but also deal with fluctuating market prices and limited resources.

Class Struggle (1995): A game explicitly focused on the struggle between different social classes, with mechanics based on Marxist theory. The game uses cards to represent different class actions, including labour strikes, class warfare, and capital accumulation. It’s a critical exploration of class conflict, making it more of a political and educational game than a typical competitive one.

Magie’s original game, The Landlord’s Game, not only inspired the creation of one of the world’s most famous board games—Monopoly—but also carried with it a powerful message about the dangers of monopolies and the importance of economic fairness. Though her version laid the groundwork for what would become a global phenomenon, Magie was sadly left out of the history books. While Monopoly became a symbol of competitive capitalism, Magie’s vision of social reform and collective prosperity remains an essential, though overlooked, part of the game’s legacy.