We’ve all seen enough people on the streets strutting about in their designer logo-ridden pajama-looking outfits, often paired with matching (ugly) footwear. If they’re so ugly, then why do people wear them? The basic explanation is that the parvenus (wealthy newcomers to the upper class) and poseurs want to climb the social ladder will often buy items that literally scream luxury names like ‘GUCCI’ or ‘BALENCIAGA’ to align themselves with the moneyed elite.

But according to ex-Guardian journalist Hadley Freeman, it’s because “they are morons” who are “merely being used by the brand as a form of free advertising.” Whichever way you look at it, the reason designer brands do it is a bit more complicated than just free advertising. Fashion writer Derek Guy of “Die, Workwear” blog explains:

The Streetwear Cred

One of the biggest reasons is that luxury brands and streetwear have been merging for the last 20 years. A lot of streetwear is heavily logo driven, and you don’t have to dig deep to see its influence on designer brands, and it goes deeper than just ugly sneakers.

Streetwear is a style rooted in hip-hop and youth subcultures, often with a quintessential look: oversized silhouettes, sporty cuts, and an unapologetic use of logos. Branding isn’t subtle; it’s the main attraction. Logos are blown up, repeated in all-over prints, or plastered across the chest in graphic fonts. Brands like Supreme, with its iconic red box logo, A Bathing Ape (BAPE) and its loud camo prints, and Off-White, known for quotation-mark slogans and industrial graphics, built their identities on turning logos into status symbols.

A key figure in bridging the gap between streetwear and luxury long before it was fashionable is Dapper Dan, the Harlem designer who in the 1980s and ’90s began crafting custom pieces using logos from brands like Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Fendi. These weren’t licensed collaborations—Dan was effectively bootlegging high fashion. By reworking classic logos into street-ready shapes—tracksuits, puffers, oversized coats—he created a look that spoke to an audience ignored by the fashion elite: Black and brown youth, rappers, and hustlers who demanded recognition and style.

Although once sued and shut down, Dapper Dan’s work was later embraced by the very fashion houses that dismissed him. In 2017, Gucci officially partnered with him (after a controversy involving a Dapper Dan-inspired mink bomber jacket that Gucci used for their Cruise collection), releasing co-branded collections and opening an atelier in Harlem. This marked a turning point: streetwear wasn’t just influencing luxury—it was redefining it.

Luxury designers soon began openly borrowing from streetwear’s visual codes. Virgil Abloh, appointed as Louis Vuitton’s menswear artistic director, brought streetwear’s graphic edge into one of fashion’s oldest houses. Demna Gvasalia of Balenciaga leaned into oversized silhouettes and ironic branding, while Alessandro Michele at Gucci turned the once-subtle GG logo into an all-over motif seen on tracksuits, sneakers, and outerwear.

As influential streetwear was, it wasn’t the only reason design houses opted for repeated logos in their designs.

Copyright Laws and Designer Fashion

In the world of high fashion, creativity abounds—but when it comes to legal protection, the rules are surprisingly limited. You see, clothing design as a whole isn’t fully protected by copyright.

The reason? Copyright law generally doesn’t cover functional items, and clothing is considered just that. Silhouettes, cuts, and construction techniques fall outside the scope of copyright. So if someone copies the shape of a jacket or the style of a dress, there’s often little legal recourse. What can be protected are the original elements that aren’t functional—such as graphic prints, logos, embroidery, or artistic patterns.

This lack of full copyright protection in fashion is exactly how high street brands like Zara and H&M can legally copy designs seen on luxury runways without infringing the law—as long as they avoid using trademarked elements like logos or protected prints. Because copyright doesn’t cover garment shapes or construction, these brands can produce lookalike versions of luxury pieces at a fraction of the price, often within weeks of a fashion show.

This legal gap explains one of the most visible trends in luxury fashion today: the explosion of logos. Since the structure of a garment can’t be easily copyrighted, fashion houses lean heavily into branding—covering clothing and accessories with distinctive, often oversized logos. These logos are protected by trademark, which gives brands a powerful legal tool to prevent imitation. It’s why you’ll see the LV monogram splashed across Louis Vuitton tracksuits, Gucci’s GG print repeated on handbags, or Balenciaga’s name blown up across hoodies.

Because of these legal constraints, luxury brands rely on a mix of strategies: copyright for original graphics, trademark for logos and brand names, and design rights or patents for unique visual elements. In short, the fashion industry’s limited copyright protection has helped make logos a visual and legal cornerstone of luxury design.

The Artificial Scarcity of Luxury

Why are luxury brands so fiercely protective of their designs? It’s because their business model often depends on artificial scarcity. Yes, some luxury goods—like an Hermès Birkin bag—require skilled craftsmanship and limited production. But when it comes to things like T-shirts? Let’s be honest—they could manufacture millions if they wanted to. The scarcity isn’t always real; it’s engineered.

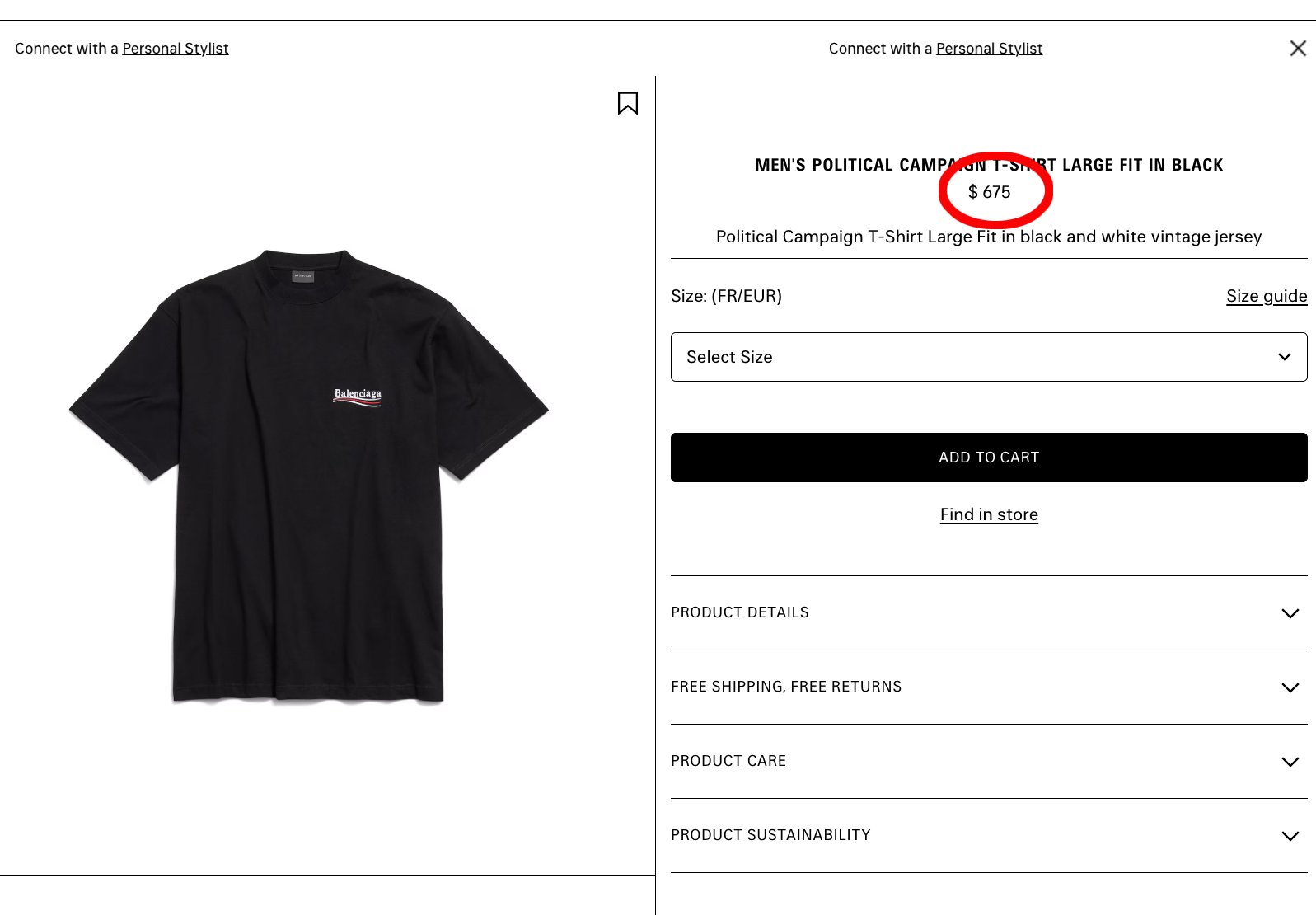

Now imagine if Balenciaga couldn’t stop counterfeiters or copycats. What if a knockoff of their $675 T-shirt was suddenly everywhere—sold on Amazon, stacked in high street shops, indistinguishable from the original? The illusion of exclusivity would vanish, and with it, the justification for premium pricing. If anyone can get it, it’s no longer luxury.

The Bottom Line

This is why luxury brands design and brand their clothes in ways that allow them to protect their turf—not necessarily through copyright, but through trademark law and aggressive legal enforcement. It’s a way to control supply, maintain prestige, and justify sky-high margins—even when the product itself is mass-producible and, let’s face it, sometimes unimpressive. Of course, it also plays perfectly into the hands of parvenus and poseurs, for whom the logo does all the heavy lifting.

The phrase “money talks, wealth whispers” neatly sums up the contrast between those who flaunt their riches and those who don’t need to. Flashy logos, gold-plated accessories, and head-to-toe designer fits often signal new money—parvenus eager to be seen. In contrast, old money tends to dress in quiet luxury: unbranded, tailored, and understated. True wealth doesn’t have to prove itself; it’s content to whisper, while everyone else shouts.